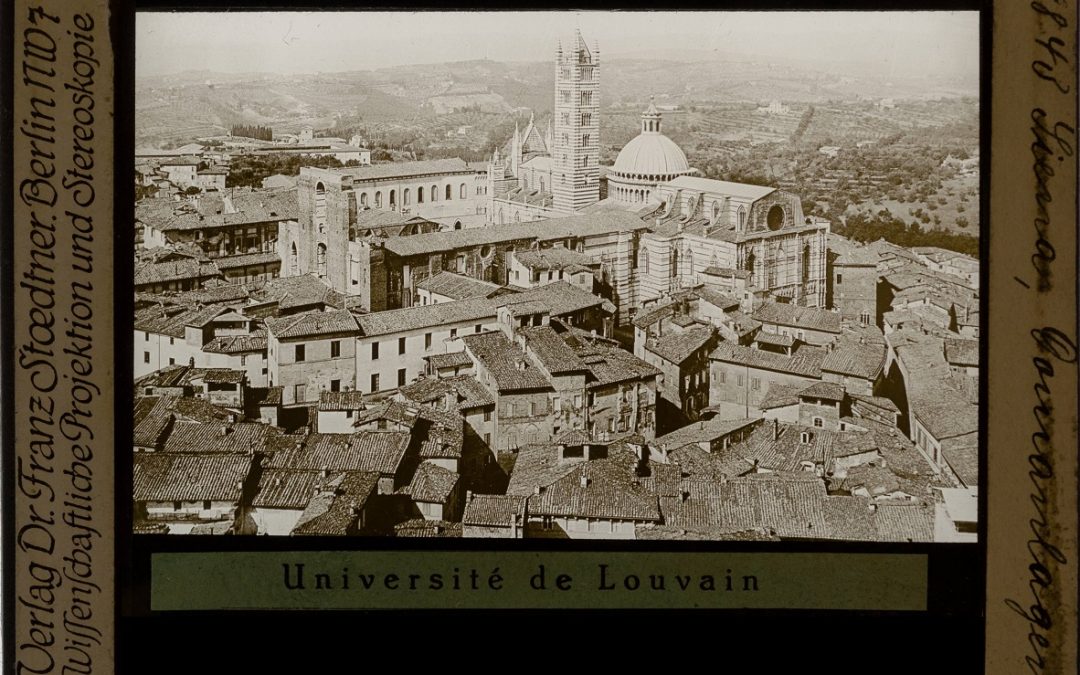

img. from KU Leuven’s collections in Europeana: glass slide depicting Siena, the panorama of Cattedrale Metropolitana di Santa Maria Assunta. Such kind of glass slides were used to teach art history at KU Leuven.

In the framework of a capacity building effort to support digital transformation of the cultural heritage sector, that is promoted within the EU-funded Europeana DSI4 project, a case study was developed by Photoconsortium, the Europeana accredited aggregator in the domain of photography, about the benefits and impact that Cultural Heritage Institutions can gain from publishing high-quality, open access heritage collections in Europeana, the European digital gateway to cultural heritage.

The case study analyses the stories, experiences and lessons learnt in the area of leveraging digital heritage content for education, deployed across many years from one of the top Universities in the world: KU Leuven.

Currently, KU Leuven’s collections in Europeana amount to ca. 34.000 cultural heritage items, complying to the highest quality levels of the Europeana Publishing Framework and completely open access, as all the images are either in Public Domain or free to reuse.

The dataset comprises a very varied collection of cultural heritage contents as preserved in the holdings of KU Leuven Libraries, including portraits, historical documents, engravings, travel photographs, educational photographs of monuments, paintings and other cultural items used for teaching art history.

From opening up Heritage collections to Digital Curation and User Engagement: the Journey of

KU Leuven Library Collections in Europeana

by Valentina Bachi (Photoconsortium), Sofie Taes, Fred Truyen (KU Leuven)

Introduction

In January 2021, a big effort was made by KU Leuven to improve and enlarge their existing dataset in Europeana. An injection of newly digitized content and an upgrade of existing records to the higher tiers of the Europeana Publishing Framework showcase that embracing the open access approach for digital cultural resources is at the core of KU Leuven’s policies.

The work on the source materials was done by the KU Leuven Digitization Lab for content and by the LIBIS team for metadata. Then the dataset was processed via the Photoconsortium instance of MINT, the aggregation software that allowed the records to be mapped and transformed to the Europeana Data Model. Finally, the records were harvested and processed with the Europeana Metis tool, which eventually allowed for publication in the Europeana portal.

Currently, the dataset consists of ca. 34,000 records complying to content tier 4 and most of them complying to metadata tier B. The combination of these two requirements make the dataset highly accessible and completely reusable. But this is just a starting point for a journey that needs to be taken for enabling these online resources to have a true impact.

KU Leuven, pioneer of digital transformation since the early days

In a very explicative post published on prof. Fred Truyen’s Digital Culture blog, the story of KU Leuven’s approach to digital transformation is depicted from the early days, when the University created a Learning Content Management System to accommodate the flux of information and documents (mainly simple PDFs) to support teaching, until the development of the current Virtual Learning Environment, where learning activities such as exercises and tasks could be done online. The next step for the digital transformation of teaching and learning at KU Leuven would be to capture what happens in the classrooms and study centres as an information stream, which would help to manage, control, and optimize these processes. KU Leuven implemented an integrated backbone architecture that supports these information processes, and helps guide its educational business deployment.

More generally speaking, in the Cultural Heritage sector it is becoming clear that the digital transformation goes beyond creating an online catalogue of the collections, but instead it is about implementing “impactful ICT infrastructures, and rethinking the core information processes and organizational workflows, to develop a coherent digital strategy to make sure their business processes and services are based on their information exchange systems”. In this light, Open Access policies are a generally accepted ingredient of cultural heritage institution (CHI) policies, for supporting the mission of sharing culture and granting access to cultural heritage.

Backending this process, the idea of “Open Access” benefitting the user communities is also expanding, and now seems to imply a long tail model, involving a majority of users just consulting and browsing the materials, and a more dedicated segment really taking advantage of this source material to create new outputs. As prof. Truyen argues, “We should think about what we aim for when people have access to our digital collections. What is the real potential? We seem to be lacking a vision about what “reuse” could mean in the context of heritage. I guess we all understand “reuse” as a secondary use, beyond the primary, private individual use. Let’s not forget that also the primary use has a long tail structure: there are communities who use the contents of digital collections in a casual, ephemeral way: “looking around” a bit or coming in on your portal in search for one piece of information. But there are the more passionate culture lovers who spend many, many hours studying the digital collections. In the end, there are professionals who actually need this content to integrate it into their work. In the case of cultural heritage collections, teachers, educators, and researchers come to mind. And fellow CHI colleagues who are looking for missing pieces, or want to build a virtual overview of dispersed collections. Once a new result, product or service comes out of this primary use we call it “reuse”. That could be a gallery, a story, a game, or an app. Open Access, exemplified by OpenGLAM is then the publishing of digital collections in such a way that people have the license to reuse this content.”

Supporting Open Access aiming at engaging communities with culture

The Open Access movement supports an approach to digital assets that makes available online resources through digital technologies, with the scope of allowing broader audiences to have access to any cultural, scientific and artistic resource, by the means of mass digitization and open licensing. This approach started with the original aim of supporting a wider flux and exchange of information among scientists for research purposes, but across time it shifted towards a more inclusive model where all types of users, and of re-uses, are enabled.

This is especially visible with digital collections of cultural heritage, that are of interest also for the wide audience and not only for specialists and researchers: anyone should be able to know and learn about European rich heritage and to access it for any purpose, with evident benefits in terms of knowledge sharing, education, mutual understanding. Actually, the European Commission has acknowledged for a long time that digital cultural heritage is a powerful means towards a richer and wider knowledge of European history and the support of the (sometimes difficult) process of cultures’ integration and of identity building for Europeans.

A bet was also made that digital cultural content free to reuse would support economic growth and job-creation. All these assumptions were turned into concrete actions not only by embracing policies for digital transformation, but also supporting the process with huge investments in projects for digitization and online access.

The EC’s flagship project that is active since over a decade now is of course the creation and maintenance of Europeana, as the European access point to European heritage: Europeana really can have a outstanding role in enabling access to and reuse of digital resources, and also offers possibilities for a democratization of historical and cultural resources, fostering knowledge circulation about all European histories and cultures, and also allowing minority communities to virtually re-appropriate of their cultural heritage, by correcting misrepresentations from predominant paradigms which are now surpassed (e.g. better understanding colonial history, or unveiling history which was suppressed and erased).

To allow this to happen, it is necessary to go beyond the possibility for users to browse/search for content and just download images, implementing a more active contextualization of the content based on users experience, and reconnecting the cultural content with the cultural community it springs from.

The potential in terms of societal progress is evident, but to unlock it is also a highly complex task: while ICT tools and all the technology supporting the digital transformation are universally acknowledged as the “enabling element” of this recipe, as the yeast in a cake, it is clear that Open Access content cannot be the only other ingredient, as Open Access content is not user-engaging or meaningful per se: there is a human factor that needs to be included in the loop. And therefore Europeana and the whole plethora of aggregating and content providing institutions really need to transform their approach to collections, by engaging communities in assisting and supporting co-curation, tagging and annotation, translations, transcription efforts on the available digital collections, all in the light of unlocking the storytelling that can be made based on the content.

This process suggests a next step of development for enabling digital content fruition, by transforming websites originally conceived as online catalogues into real participatory platforms that allow people to engage with the contents, un-burying and narrating the meanings and values that the digital collection represents. For this reason, the Europeana tier 4 requirement (good resolution + open reuse license) is just the starting point for a journey that implies a multidisciplinary effort of curation, both on the metadata side – by offering rich and relevant information that allows for the content of interest to be retrieved and interlinked, and on the co-curation and storytelling side – and by enabling users to associate interesting meanings to the content itself, and to share these meanings with others.

As a policy, KU Leuven Libraries decided that all published contents that are identifiable as Public Domain should be labeled and published as such. Where we actually still own the rights as KU Leuven on published heritage content we would add a CC-BY label where possible, and of course use the Orphan Works directive as implemented in Belgian law when needed.

In KU Leuven, a unique collaboration developed between CS Digital, the research unit on Digital Transformation of the Faculty of Arts, the University’s Imaging Lab, specialized in high-end digitisation of Heritage objects, the LIBIS Library automation service, the Special Collections, the KADOC documentation and research centre, as well as the MA study programmes of Cultural Studies and Digital Humanities. These efforts relied on the work for the DSI and on project funding from the Connecting Europe facilities Generic Services programme.

Focus on engagement for formal and informal education

The broader scope of KU Leuven’s digital transformation is of course focused on fostering a digital transformation of education practices and resources, for a more modern approach to teaching and learning. Successful examples such as the Historiana website, the various Europeana MOOCs for reusing online cultural resources in a teaching context, or the resources made available for teachers and students in the Europeana Education environment, showcase the immense potential of digital cultural heritage available online to reach the most varied audience. A top University as KU Leuven cannot but be the top player in this field, and the number of projects done and ongoing to experiment the role of digital cultural heritage in communities engagement and in education demonstrates the effort. In collaboration with Photoconsortium, that next to being an Europeana accredited aggregator is an association of important institutions and archives in the area of photographic heritage, KU Leuven is indeed trying to develop methodologies and success stories that would bring education to the next level.

The most recent project to this aim is Citizen Heritage (2020-2023), a Strategic Partnership project funded by the European Commission in the framework of the Erasmus+ Programme. Citizen Heritage aims to provide Higher Education Institutions with novel approaches to include citizen science activities into Higher Education Institutions curricula, teaching and learning activities. Students and teachers can find a selection of good practices on how to benefit from knowledge circulation in and outside academia and how to adopt a more vibrant role in civil society. Firstly, Citizen Heritage maps and critically assesses current participatory practices in cultural heritage; then, it develops a new methodology tested with different applications in a range of workshops. Citizen science in cultural heritage is demonstrated through the application of crowdsourcing and co-creation practices, where different types of communities are engaged with local and European cultural heritage contents. Eventually, lessons learnt are shared about the role of digital technologies in facilitating crowd science in cultural heritage and education.

Citizen Heritage addresses researchers in the field of cultural heritage, including PhD and Master students from different areas, i.e. Cultural Studies, (Art) History, Memory studies, Digital Humanities, Cultural Economics and Software Engineering. These methods and activities will teach students how to take sustainable and economically viable decisions when engaging citizens, also in collaboration with cultural heritage institutions. Other stakeholder communities will be involved in Citizen Heritage too, including amateurs, culture enthusiasts and non-specialized citizens.

Citizen Heritage was conceived following the footprint of another EU project funded in the framework of the European Year of Cultural Heritage, WeAre#EuropeForCulture (2019-2020), where co-creation events based on a mix of crowdsourced heritage items and collections available in Europeana took place in various European cities, engaging local communities for embedding their “local” histories in the bigger picture of European history by creating a pop-up exhibition. The project was very successful by reaching thousands of European citizens, and concluded with a prestigious final event at the House of European History in Brussels.

Closer to the Europeana ecosystem, various Generic Services projects experiment or experimented with ways to reuse digital content in Europeana under thematic frameworks which help enabling user engagement, also in the light of formal or informal education.

- The recently concluded Fifties in Europe Kaleidoscope (2018-2019) invited people to re-read the history of the 1950s in Europe as witnessed in photographic heritage, by challenging their perception of the period as unequivocally bright and happy and its historiography as unified or uniform. Among other outcomes, this project produced a MOOC in collaboration with the other GS project Culture Moves, entitled “Creating a Digital Cultural Heritage community”, repeatedly run on the KU Leuven’s edX platform.

- Currently ongoing, Europeana XX: Century of Change (2020-2021) is implementing a wide range of activities for exploring the stories from recent history, including the publication of compelling Europeana editorials (blogs, galleries, a virtual exhibition, podcasts and vlogs) and a programme of activities such as co-creation sessions, crowdsourcing, subtitle-athons.

- Across 2021-2022, WEAVE is a GS project that is thematically focused on intangible heritage, with development of methodologies for reconnecting and co-curating minority heritage content dispersed across different countries, and where Europeana can really have a role for a virtual re-appropriation of heritage.

- Another project in which KU Leuven is involved as associate partner is PAGODE – Europeana China (2020-2021), thematically focused on Chinese heritage preserved in Europe where a crowdsourcing campaign for collecting additional tags and keywords on digital cultural heritage content in Europeana was launched in Autumn 2020, and is used as a homework and curricular task for master students…

An important aspect of the role that KU Leuven, as a university, can take up in such projects is its access to related teaching as well as students. In the four projects WeAre#EuropeForCulture, Fifties in Europe, Century of Change and PAGODE, student groups of the MA in Cultural Studies worked for their Cultural Policy practice class on projects of digital storytelling, exhibitions and user engagement with the collections.

- For Century of Change, students prepared work on the subtitle-a-thons, while other groups organized an online exhibition on the “Pill Expo” as well as a physical city tour in Leuven on the theme of “Women on the Move”, using an interactive screen application based on the MuPOP application.

- In Kaleidoscope, students organized a physical exhibition as well as a photo competition.

- For PAGODE, the students participated in an annotation sprint on the CrowdHeritage platform and a video competition fostering user engagement by challenging contestants to visualize their perception, impression, emotion and interaction with China-related digital heritage objects.

Another CEF project that needs to be mentioned, given its key connection to the aggregation work in the DSI, is Europeana Common Culture, in which KU Leuven was responsible for policy development. Quite early on in the project it was decided to connect this work to the activities of the Europeana Aggregators’ Forum, as in Common Culture only National/Regional aggregators were involved, and no Domain/Thematic aggregators. However, it was important to make policy recommendations to the DCHE that reflected the whole of the aggregation landscape. Due to KU Leuven’s membership of the thematic aggregator and DSI partner Photoconsortium, it was well positioned to lead this activity. Ultimately, the project delivered important recommendations to the EC member states, through the channel of the DCHE, on the importance of aggregation and the need to strengthen national investment in digitisation.

As a follow on to this policy work, KU Leuven joined the H2020 inDICEs project, which aims to develop recommendations on new business models and indicators for Cultural and Creative Industries and Cultural heritage institutions. KU Leuven leads the work on a self-assessment tool.

Metadata improvement

While the role of the human factor is particularly evident for good storytelling, it is also crucial on the side of information (to be) attached to digital objects. Nowadays Artificial Intelligence and Natural Language Processing techniques are appropriately cheered for enabling smoother automated metadata enrichment and interlinking. But to be effective and reliable they must be based on a structured semantic background, because the algorithms are as much intelligent as we teach them to be. For this reason, specialized expertise and domain knowledge is needed in order to identify descriptive keywords depicting a particular digital heritage object. Keywords must include both very specific terms and broader terms, in order to enable users with different levels of knowledge to interact with the digital object.

As an example, looking at a picture of a Chinese vase, expert viewers could describe it as Sancai ceramic from the Tang period, decorated with the Hu pi ban glazing also known as “egg and spinach” or “tiger skin pattern”. All these keywords should therefore be included in the metadata. But less expert users would perhaps never seek for Chinese cultural heritage content by using such specialized keywords, and thus the digital object needs to also be associated with more generic keywords, for the object to be retrievable. Sinologists would be needed to transfer the expertise into the metadata. On the other hand, it doesn’t take a highly specialized curator to attach the term “vase” or the location “China” to the digital object: anyone can do that.

This is where crowdsourced annotations and AI can really help CHIs, by adding – with almost zero effort – more general or generic keywords, easy to detect for any human eye or for visual recognition algorithms. This would mean that while rich and descriptive metadata, also very specialistic ones, are certainly needed at the source (this implying a planned workflow of the curating institutions based on historical and semantic research), further iterations of enrichment (both by AI or by human ‘co-curators’ basing their contributions on a predefined list of terms) allow to enrich the metadata for large collections in order to make the content more retrievable and reusable.

Layered information, multivoice storytelling: building digital curation expertise

All KU Leuven’s endeavours towards the sharing and distribution of its digital collections, serves a twofold aim: one is to promote the collections as the valuable and unique cultural heritage sources that they are; the other, to foster its educational practice with material that sits at the university’s core.

In order to provide curators, educators, students as well as the wider community of cultural heritage community with the necessary tools and triggers to explore and enjoy the collections, the creation and constant care for layered information contextualizing not only the collections but every single item included, is of vital importance. As described above, combining low-threshold, generic keywords with highly specialized metadata results in the layered information package that each user type can unwrap according to their profile and specific objectives. A researcher might need very precise period designations, material descriptions, technical specifications and names of people involved in the creation and preservation of the (digital) heritage objects; but a student might be looking for suitable imagery illustrating a thesis, a piece of creative writing, or a social media project. The culture enthusiast, in turn, might be enticed to venture into the realm of digital collections by a small selection of outstanding and striking pictures.

As a knowledge institution, harbouring educational and research activities, but also as a carrier and harbour of centuries of tangible/intangible heritage, it is KU Leuven’s aim to serve all such purposes and target groups. Therefore, the university considers it not only good practice but a compelling duty, to continuously develop advanced and innovative storytelling practices, leveraging on the ever improving data/metadata quality. This entails exploring novel formats, such as the vlogs (narrated blogs compiled out of vintage photographs and videos, with music and voice-over), the podcasts (audio-stories mixing narration with interviews, music and soundbites) and interactive, hybrid pop-up exhibitions (smart screens individually operated by users’ smartphones, to be placed in public spaces) mentioned above.

With a view to future efforts, KU Leuven intends to not only pursue this path, but also to continue facing the challenges and exploring the opportunities of partnerships, inclusive actions and participatory activities. Co-creation, not only among specialized institutions from the world of academia and GLAMs but also from the end-users, is among the main focal points: how can we take heritage collections back to the community they originated from? How can we help them unfold their stories, as a counterpoint to history canon? And how can we tie the digital cultural heritage knot in such a way, that the ultimate destination (end-user) also becomes the very nucleus of the university’s underlying heritage policy?

Aggregation

While KU Leuven contributed collections to Europeana already in the scope of the project Europeana Inside, the largest contribution came with the project Europeana Photography, in which KU Leuven led a consortium contributing about 450,000 high-quality images of the first 100 years of photography to the online photography collection of Europeana in the period 2012-2015. From this project, which used MINT to ingest collections into Europeana, the accredited aggregator Photoconsortium emerged.

For its original Europeana Photography contribution, KU Leuven opted to export data from its library database in MARC21 format, and then convert these data using MINT with a MARC-to-LIDO and subsequent LIDO-to-EDM translation script. LIDO was chosen by the project as a common intermediate format. As for the metadata scheme, an enhanced EDM data model was shared among project partners, and a Photo thesaurus was developed to enrich the data.

The further story of KU Leuven’s work in feeding data to Europeana might be a stark reminder of the problems that many organisations face when contributing to Europeana.

Contributing to Europeana is by no way the core mission of KU Leuven, which is not a Heritage institution (two renowned Heritage institutions recognized at the Flemish level do form part of the university: the Special Collections and the Maurits Sabbe Library). This means the data translation from KU Leuvens’ library – serving more than 10 thousand researchers and more than 80,000 students – was only a project-funded side activity. Therefore, when an upgrade of data and delivery of new data was envisaged a few years after initial efforts were made, quite a few issues arose:

- The staff member who once made the MARC output, enriched the metadata with the Photo thesaurus – using offline scripts – and oversaw the MINT process, left the university, leaving behind only scarce documentation.

- In the meantime the University changed and migrated the underlying library management system (currently ALMA).

This meant that the original data transformation scripts did no longer work, and a new MINT mapping needed to be made. In fact, it is planned to make a generic ALMA to Schema.org mapping at the university, so that we can deliver not only to Europeana but also to other aggregation services. We would then implement an Schema.org-to-EDM conversion.

Under time pressure for the DSI-4, it was decided however to just make a new MARC export. As the implementation of the Photo thesaurus as a SKOS file served through HTTP is obsolete – there is no underlying Triplestore database, which makes that the service doesn’t dereference requests – it was decided to drop map, within the DSI effort, the thesaurus to Getty AAT and provide this conversion table to Europeana. The enrichment now takes place at the Europeana side and the enriched SKOS classes were stripped from our output.

Of course, we will continue KU Leuven’s efforts to generate a Schema.org compliant output. Within the DSI, we also made the effort to increase the content quality to Tier 4 where possible, and the metadata quality to Tier B.

Conclusions

Publishing collections into Europeana could in no way be considered a “core” mission for a University as KU Leuven and its libraries and archives, which are meant in the first and foremost place to support Research and University teaching and learning.

However, embedded in the university are two renowned Heritage Institutions: the Special Collections and the Maurits Sabbe Library. The Imaging Lab of the University provides high-end digitisation expertise. Together with CS Digital, a Research Unit in Cultural Studies specialized in Digital transformation of the Heritage sector, there was the opportunity to deliver high-quality contents to Europeana.

It is our strong belief that publishing these open collections serves our core missions – research and education – in an excellent way. On the basis of the work done in the DSI in collaboration with accredited aggregator Photoconsortium, we were able to prove this effect in many CEF funded digital projects in which we were able to explore, together with our MA level students, how heritage can be opened up to communities to stimulate genuine engagement and even citizen science efort. In this, Digital curation proved to be key, and this became a core competency developed at CS Digital.

As a takeaway, we think open publishing should not be considered as a side activity of which the supporting activities are merely funded on a project basis, but should be part of the digital strategy of the university library. This involves an integrated support for Linked Open Data standards and metadata enrichment.